Discussions about education tend to focus on those who do the teaching. Let’s not ignore, however, the abundant opportunities for improvement possible at the point of learning. Amy and Mike invited educator Patrice Bain to explain the importance of feedback-driven metacognition.

Discussions about education tend to focus on those who do the teaching. Let’s not ignore, however, the abundant opportunities for improvement possible at the point of learning. Amy and Mike invited educator Patrice Bain to explain the importance of feedback-driven metacognition.

Find the audio file and show notes for this episode at https://gettestbright.com/feedback-driven-metacognition.

Amy Seeley 0:04

Welcome everyone. I’m Amy Seeley, president of Seeley Test Pros, helping students to succeed at all kinds of tests from eighth grade to grad school in Cleveland, Ohio.

Mike Bergin 0:12

And I’m Mike Bergin, president of Chariot Learning, helping students with tests, school, and life, based out of Rochester, New York.

Amy Seeley 0:18

Between the two of us today, we have over 55 years of experience at the highest levels of the test preparation and supplemental education industries.

Mike Bergin 0:25

We both love to talk and learn about the latest issues in education, testing and admissions. So let’s get down to Tests and the Rest. The fascinating topic we want to explore today is feedback driven metacognition, but first, let’s meet our special guest, Patrice Bain.

Amy Seeley 0:41

Patrice Bain is a veteran K-12 educator, speaker, and author. As a finalist for Illinois Teacher of the Year and a Fulbright scholar in Russia. She has been featured in national international podcasts, webinars, presentations and popular press, including Nova and Scientific American. In addition to powerful teaching. She also co-authored the essential practice guide for educators organizing instruction and study to improve student learning in collaboration with the Institute of Education Sciences. Her latest book is A Parent’s Guide to Powerful Teaching, reinforcing the teacher triangle of student, parent and teacher collaboration. Welcome!

Patrice Bain 1:18

Thank you so much for having me, Amy. And Mike, I’m really excited to talk about metacognition today.

Mike Bergin 1:26

Patrice, we are really excited to talk about metacognition today as well, these are among our favorite topics to cover. But before we get into that, you have such an illustrious background in education, we would love to hear a bit about your travels, your path and how you wound up where you are today.

Patrice Bain 1:48

Wow. That’s a great question, Mike. You know, I started teaching back in the 1990s. And I couldn’t figure out why some of my students did really well, and some didn’t. And I had been teaching for about 10 or 12 years, and there was no place for me to go to find that answer. You know, up until 2006, most research on learning was done at universities, with college students in laboratories. And there wasn’t anything that applied to my middle school classroom. Plus, it was all in journals tucked away in ivory towers. And then just, you know, sometimes you’re just in the right place at the right time. And I happened to meet two cognitive scientists who wanted to investigate, well, how do kids learn in an authentic classroom? And that classroom was mine. So it was the first in the United States where we actually looked at how children learn. And then the rest? Well, you read the rest.

Amy Seeley 2:56

That’s amazing. But it’s true coming up in getting my education degree right in like the early 90s. You’re right, there really wasn’t. I feel kind of bad looking back. I didn’t get any of that. So that’s why these last few years talking with people like you, it’s amazing how much is coming out of the research and the science behind how students learn.

Patrice Bain 3:16

Yes, absolutely.

Mike Bergin 3:18

I think it’s an excellent point that educators who grow frustrated with not seeing their students learn are well served to start asking questions about the interplay between teaching and learning. And that leads us to our conversation today. Feedback driven metacognition sounds like jargon. It sounds like something very technical, but, in fact, we’re gonna get to that it’s actually really fundamental. And I think Patrice, the best way to start this process, is to look at the relationship between the time that a student spends learning or studying or reading or looking at a book because we really don’t know what they’re doing. It doesn’t necessarily equate to the learning that they derive from that activity. You’ve experienced that. You’ve observed that. Can you tell us a bit about the phenomenon?

Patrice Bain 4:16

Absolutely. And, you know, it is so frustrating for students, for teachers, for parents, when they have seen their child study, and study and study, and yet they still don’t do well. And you know, we now know why that happens. And it has to do with metacognition. And I define metacognition as you know what you know, and you know, what you don’t know. And, too often, we don’t help our students identify what they don’t know.

Let me give three examples. So, first is the example of the student who studies so, so hard, but doesn’t do well. And they become so frustrated that eventually they quit studying it. They start to internalize failure, when we simply have not taught them about metacognition. When they study, it’s often because they study what they already know. And it brings forth this illusion of confidence. I know this, I know this, I know this, I don’t know that. So I don’t spend time on that. So we really always have to be able to provide our students with strategies. Another example is, just because you see something doesn’t mean you know it.

Amy Seeley 5:47

The illusion of knowledge, right?

Patrice Bain 5:51

Yeah. So just, you know, don’t look at any devices. But if you have paper in front of you, draw the Apple logo. Could you do it?

Mike Bergin 6:04

Right? A lot of people think they know, because they’ve seen it a million times. A lot of people proudly carry Apple products, and yet, not everybody’s gonna get it right, they’re not going to get it pointed in the right direction, and are going to get the right shape. It’s true.

Patrice Bain 6:18

So just because you see something doesn’t mean you know it, and so often things like that lead to ineffective study strategies. Even the terminology we use. Oh, go look over your notes. See where you highlighted. I mean, we’re using the see words looking. And the third example is, sometimes, we think we know something, when we don’t. So, if I were to ask a question, what is the capital of Australia? Is it Sydney, Canberra, or Melbourne? And you might think, right away, well, I’m pretty sure it’s Sydney, or, oh, I know, it’s not Sydney, it’s Melbourne. But actually, it’s Canberra. And so sometimes we think we know an answer. But we don’t. And sometimes we have our students think that they know something when they don’t. And that is another illusion, an illusion of fluency. And feedback driven metacognition is the key to helping rid those disconnects with illusions.

Mike Bergin 7:36

So, walk us through this. We know that these illusions exist, we know that students will spend time in the areas where they’re most comfortable. They will think they know things because they looked at those things, they saw those things. How can we discriminate between what we know and what we still need to know?

Patrice Bain 7:58

I always started the first day of every school year saying I am your teacher, and I’m going to teach you how to learn. And metacognition was one of the first things that I would teach, because I would simply ask on that first day, “Have you ever studied hard for a test but didn’t do well?” and 99% of the hands go up when that happens. So when you have the confidence of knowing how to learn, you know, something else I like to say is, you know, we’ve been taught how to teach, but we haven’t been taught how we learn. So when we learn how to learn, and we can instill that with our students, you know, then they become active participants and invested.

But I kept seeing this disconnect. So I created what I call the four steps to metacognition. So bear with me while I go through them.

First of all, no notes, no screens, no information in front of you, except possibly a study guide or flashcards. The first step is to decipher, “ do I know it or not?” That’s a JOL, or a judgment of learning? And I would encourage my students to just go through everything they need to know on that sheet. Do I already know it or not? If you know it, put a star or a happy face and if not a question mark. That’s step one.

Step two. Now go ahead and answer all those you know.

Step three is the first time that you use your books or notes and look up what you don’t.

And step four is to verify that, what you thought you knew, you did. So, it’s not a Melbourne or Sydney situation. So the four steps judgment of learning, do you know it or not? Right? answer those, you know, look up those you don’t and verify. So, the beauty of this is the students go through those four steps. And at the end of the four steps, they have already identified those areas that gave them some trouble. So when they study, they go back and they study the question marks. It is so easy, it can be used in every type of class. And, you know, but first, explain why this works to your students. And then they’re gonna find that they are so much more effective and efficient in their studying.

Amy Seeley 10:52

Now, that’s 100% true, because really, I think what you’re describing is this idea of working smarter, not harder. A lot of us know, especially from parents talking about he studies so much, he’s putting so much time in. And so it’s like, you want to reward the fact that a student is so committed, but at the same time, that inefficiency is problematic, right? Because you want to be able to sort of, if you’re going to learn something, you want to do it as quickly as you can. But I also find it’s this idea that students don’t properly identify what they don’t know, in which case, they’re not studying the right things. And also, they’re not testing themselves, right? They’re not assessing that verification you’re mentioning is when did you verify if you knew it. Oftentimes, Mike and I see this with our students. The verification is when they show up to take the test. It’s like, no, no, no, no, it’s got to happen before you show up on test day to make sure it’s up there.

Patrice Bain 11:44

Right? Yes, it has to be the entire process, where students have the opportunity to retrieve throughout the course, before the big high stakes test.

Amy Seeley 12:01

So, there are some important principles we know that are involved in this process you are describing. One of which is retrieval. Another might be spacing. Tell us a bit more about how our retrieval, spacing, or metacognition, how are they connected?

Patrice Bain 12:17

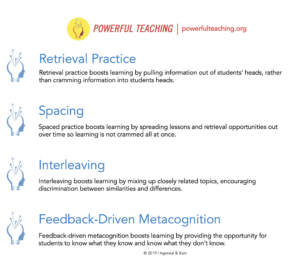

They are all connected. So, first of all, let’s talk about the three steps of learning. The first step is encoding. And that’s getting information into your heads. And as teachers, we excel at this, we know our curriculum, we know precisely how to get information in. And step two is storage. So we have encoding, and then we have storage. And often our teacher ed programs kind of end at that. You know, it’s our job to get it in and there it is. But my co author of Powerful Teaching, Dr. Pooja Agarwal, has this great quote, and it is too often we focus on getting information in. What if instead, we focused on pulling information out. And that is the third step, retrieval. Encoding, storage, and retrieval.

We know through robust research that, in order to know something, we have to be able to retrieve it. And it’s like this cycle. We know that as soon as we learn something, we start forgetting it, which is kind of dismal for teachers, right? But there’s something called the forgetting curve. And it helps us realize that one of the best ways to learn is to space out retrieval.

So, I identify spacing as revisiting retrieval. So you teach something, and then 24 hours later, I have a question about where the students have to retrieve. A simple way to do that as a teacher, like too often we might say, Okay, class, remember yesterday, we discussed blah, blah, blah, well, that’s encoding a simple shift in what we’re doing. Okay, class, yesterday, what did we talk about? Give them about 15 seconds to think. Pair them with a partner, do a group share, and you have a room absolutely rich with retrieval. So you do the retrieval, you space it, ask about the important things 24 hours later, and then again in a few days, and then maybe again in a week. And you know, this can be as easy as a blast from the past question. I love to do these with my students. I’d say, Okay, it’s time for a blast from the past. And you would simply throw out a question.

Now what were those three steps of learning, and give them an opportunity to retrieve and really simply go on. But what you’re doing is you’re allowing retrieval, but you’re also allowing students to identify if they know the answer or not. So a blast from the past mini quizzes, there’s all sorts of strategies that I came up with that really help students with their metacognition. It’s like a circle. In order to really have robust learning, you need to retrieve, you need to space out the information, and you need to have students be able to identify if they know it or not.

Amy Seeley 15:59

And I think that’s one of the challenges that Mike and I see is that, in our line of work, we are getting students, oftentimes, many years after some of that information might have been in, encoded. So the dilemma is that there has not been that space retrieval over time, in which case, knowing punctuation rules or knowing geometry concepts. And so it’s getting students to realize, you’re gonna have to go back, review, you know, assess and do it repeatedly. It’s not just looking over and on a sheet of paper one time and expecting it to be there. I think it’s also why parents get frustrated, because they don’t realize that, just because their student got an A on a test or an A in the semester, that doesn’t mean that students can carry that knowledge with them into the future, which is oftentimes what standardized tests do is they expect to see what you know, but much farther into the future than most families would probably realize. It’s got to stick with you.

Patrice Bain 16:58

Yes. And so that’s another reason why I think it’s so important to have communication with the parents. So they understand that, yes, they got 100% and an A on that test, but a week and a half later, it’s as if, where did it go? So helping parents understand that and also being able to, for younger, you know, well, I would say high school on down, if teachers would simply send a note, you know, however you communicate with parents about, this is what we learned today, or this is what we learned yesterday, here’s a question you can ask, and here’s the answer. And so what happens, rather than a parent saying, Well, how was your day today? Because we know the answer, that’s gonna be, but instead, you know, parents being able to ask, you know, here’s a question from history.

Amy Seeley 18:02

Be specific with what you’re asking, because of course, having that conversation that actually can further cement the memory, because there’s an opportunity to talk about it or recreate it for sure.

Patrice Bain 18:14

Absolutely. Because then just asking that simple question that the student is retrieving the answer. And the parent knows what the answer is. You could do this with, you know, friends or whatever. But it’s that all important, being able to retrieve and getting the feedback that yes, it’s correct. And the wonderful thing about too is, when you work with somebody asking a point blank question, it will usually then bring forth more material related to that concept. And our goal is to get it from working memory to long term. And so this is all the process of learning.

Mike Bergin 18:57

So Patrice, you know, you just gave a couple of pieces of advice that were targeted towards parents and teachers. And I think that we as educators all feel a bit of frustration that we’re teaching but our students don’t necessarily seem to be learning. Who’s ultimately responsible for learning outcomes. Is that the parent?

Patrice Bain 19:19

I came up with what I call the responsibility diagram. And I would show this to my middle school students every year, and you can sometimes hear little gasps in the room. Picture a Venn diagram, and on the left side is a teacher and on the right side is the student. The teacher is the one responsible for the encoding or the parent, teacher or parent responsible for the encoding. We are the ones that get the information in, but ultimately, it is only the student who can retrieve, not their parents, not their friends. Not Google, not Alexa. The only person who can pull that information out is the student. And, I would often have students look at that and, and be kind of in disbelief that you mean if I don’t do well on a test, it’s because the teacher didn’t teach it well, or, you know, all the other excuses that come out. But no, the responsibility diagram shows right where it is.

Amy Seeley 20:42

So, how can teachers and learners both harness feedback driven metacognition?

Patrice Bain 20:49

Well, I came up with this over the years. So I worked with cognitive scientists for about 15 years. And so, you know, first we started studying retrieval and spacing and interleaving, and metacognition. So I was able to take this research, and really work for years perfecting for me, strategies that really helped my students. So if you go to www.powerful teaching.org/resources You can download all my templates for free of the strategies that will really aid your students with their metacognition. So a quick example, flashcards, you know. I used to give flashcards: you give the term and then they go ahead and look it up in the back of the book, and they turn them in and they get 100%. And nobody could give a single definition when we talk about it, right? And so I turned those into retrieval cards, where I would simply have the term or a definition/ They would go through those four steps. Do you know what or not, answer those, you know, look up those you don’t verify those that you do? And so they’re flashcards. You know, I didn’t have to grade those, because the students were doing the work and giving themselves the meta, the feedback for their metacognition. So retrieval cards, I came up with metacognition sheets that still use the same approach. Power tickets.

Mike Bergin 22:32

What is a power ticket?

Patrice Bain 22:33

A power ticket is something that combines… in my book, Powerful Teaching, we talk about retrieval, spacing, interleaving, and metacognition as power tools, because they’re so important in learning. And my power ticket is simply being able to do a retrieval of what we did today, yesterday, last week, last month, last quarter, last semester. And so as the teacher, you are in charge of whatever topic you want to have the students answer.

I would usually have my students answer one and then find a partner who had a different one, and we would do group shares. But what I’m doing, I would pick the topics, so that all of the information kind of consolidated. So a quick example, say we studied many different revolutions. I taught world history. So by talking about, you know, the different revolutions we studied today, yesterday, last week, last month, you can start asking these really all important essential questions, such as, “how did the lives of working people change as a result of the revolution?” And they can go through each of the revolutions. And what you’re doing is providing these pathways to long term learning that really help critically think and really deep level thinking. So these are just some of the strategies.

Another thing I added is retrieval testing. If the students are, you know, reading a text or watching a video clip, or there’s an article, simply stop, close the book, turn off the screen and write down two important things you just read. That to me

Amy Seeley 24:41

That to me is the intentionality and I think that’s part of the dilemma that I see is that I don’t think students because they don’t understand the metacognition. They don’t understand that to be intentional about something I want to learn. I just did this with a book that we’re reading for Book Club about what’s influencing students and I literally closed the book and stopped myself to remember, there were four things. They each started with a D, three of them were D like I, because I thought to myself, if I don’t do this exercise with myself, I will not remember. And I think that’s the dilemma for students: a lot of times they just are not intentional about it, in which case, they think they’re gonna remember because they’ve heard it and it makes sense. But as we all know, like you said, an hour from now a day from now a week from now, poof, gone.

Patrice Bain 25:32

Right. And, you know, the teacher is still in charge. And you know what you want your students to walk away with at the end of class. So the teacher is also very intentional about when to put those pauses in. And there you go, you know, by the end of class, they have great retrieval. You could then turn that into a metacognition sheet where they could go through the four steps. I really think one of the keys though, is to really like I said, I’m your teacher, and I’m going to teach you how to learn. So the students see how it’s all connected.

Mike Bergin 26:15

And ultimately, what their responsibilities are, right? I love it. Listen, Patrice. We could obviously talk about metacognition with you all day. Unfortunately, we are out of time. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Patrice Bain 26:29

Ah, thank you for having me talk about one of my favorite subjects. Lucky me.

Mike Bergin 26:36

Lucky for all of us! If listeners would like to get in touch with you, what’s the best way for them to do that?

Patrice Bain 26:41

Go ahead to my website, www.patricebain.com. You can also get my strategies at www.powerfulteaching.org.

Amy Seeley 25:23

Awesome! We hope you enjoyed this discussion as much as we did. Be sure to join us for another fascinating topic and guest on the next Tests and the Rest!

Remember, you can find the audio file and show notes for this episode at https://gettestbright.com/feedback-driven-metacognition/.